The Voice of Inspiration: Ania Tomicka

INTERVIEW WITH ANIA TOMICKA

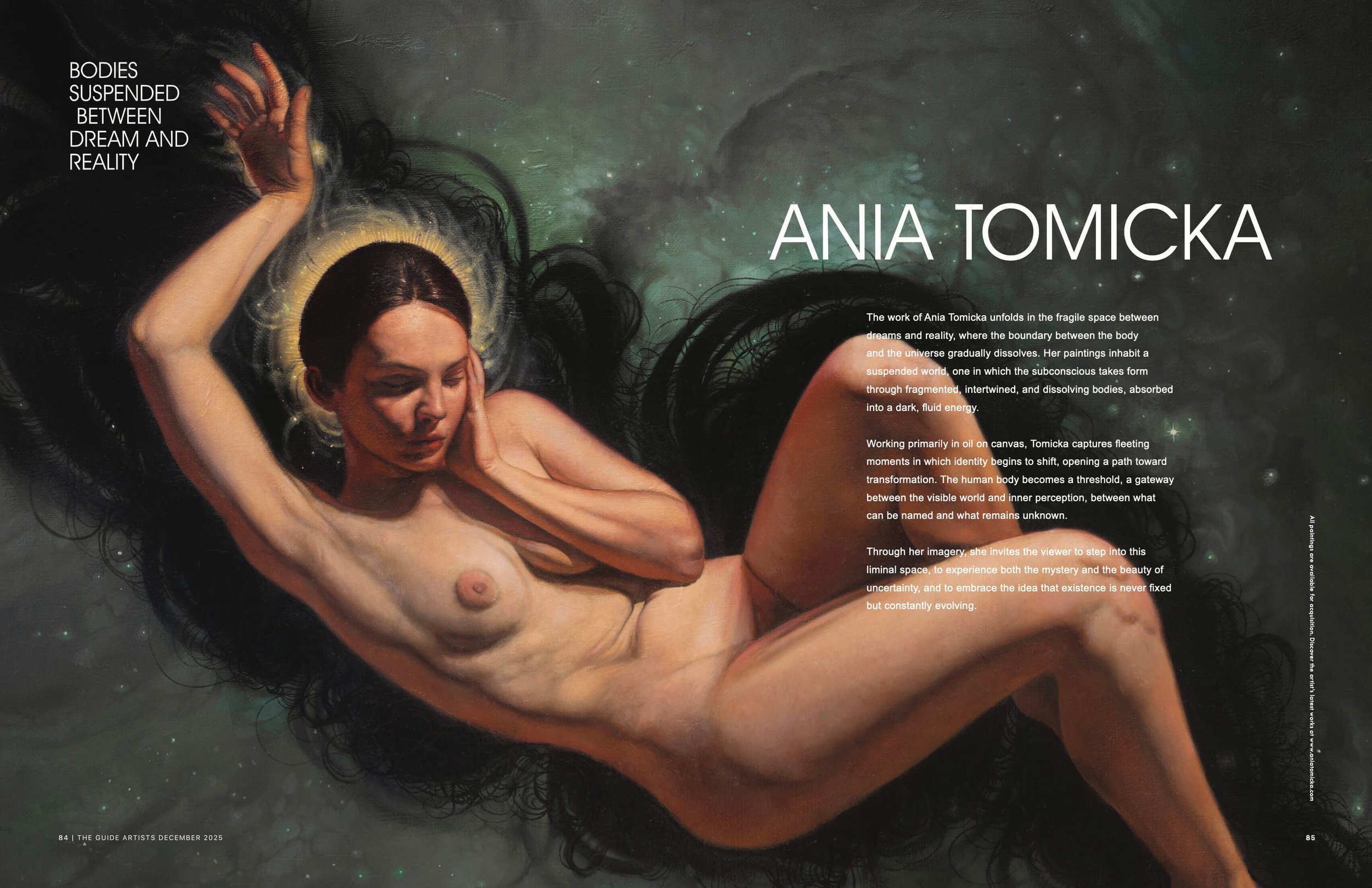

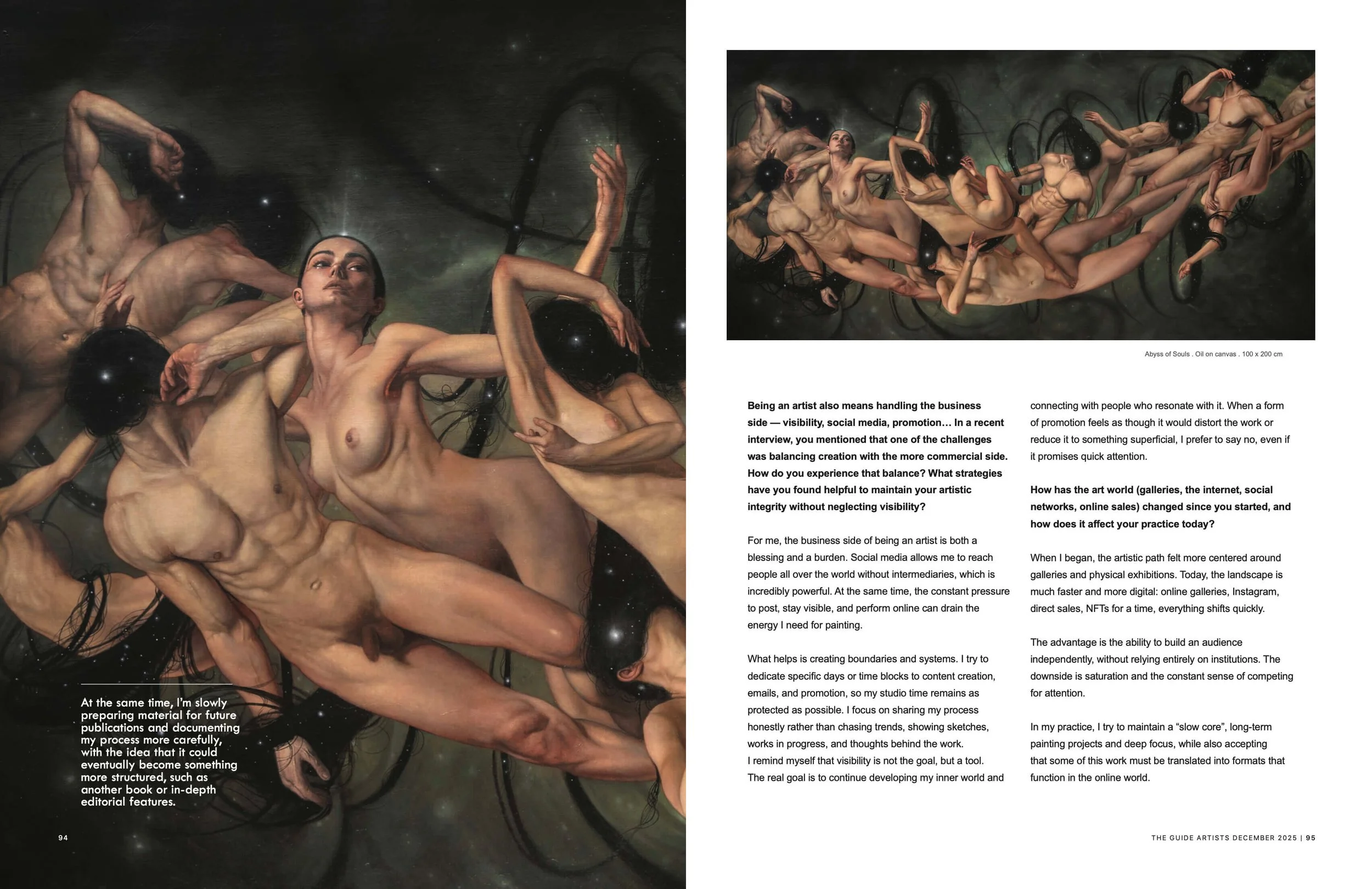

The work of Ania Tomicka unfolds in the fragile space between dreams and reality, where the boundary between the body

and the universe gradually dissolves. Her paintings inhabit a suspended world, one in which the subconscious takes form through fragmented, intertwined, and dissolving bodies, absorbed into a dark, fluid energy.

Working primarily in oil on canvas, Tomicka captures fleeting moments in which identity begins to shift, opening a path toward transformation. The human body becomes a threshold, a gateway between the visible world and inner perception, between what can be named and what remains unknown.

Through her imagery, she invites the viewer to step into this liminal space, to experience both the mystery and the beauty of uncertainty, and to embrace the idea that existence is never fixed but constantly evolving.

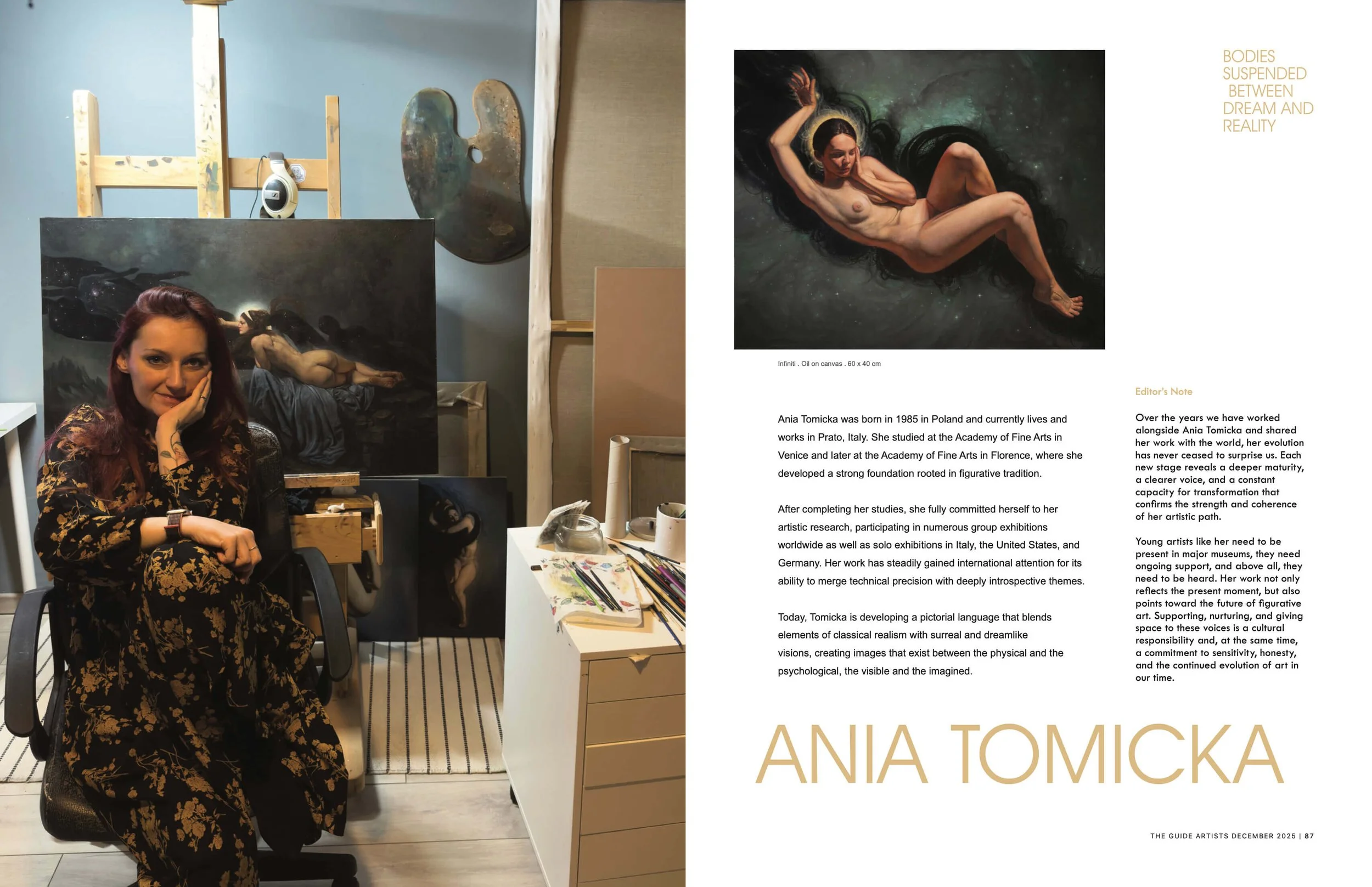

Ania Tomicka was born in 1985 in Poland and currently lives and works in Prato, Italy. She studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Venice and later at the Academy of Fine Arts in Florence, where she developed a strong foundation rooted in figurative tradition.

After completing her studies, she fully committed herself to her artistic research, participating in numerous group exhibitions worldwide as well as solo exhibitions in Italy, the United States, and Germany. Her work has steadily gained international attention for its ability to merge technical precision with deeply introspective themes.

Today, Tomicka is developing a pictorial language that blends elements of classical realism with surreal and dreamlike visions, creating images that exist between the physical and the psychological, the visible and the imagined.

You were born in Łódź, Poland, in 1985, and at the age of nine you moved to Italy, where you began drawing more intensely. What do you remember from those early years in Italy, and how did they influence your decision to become an artist?

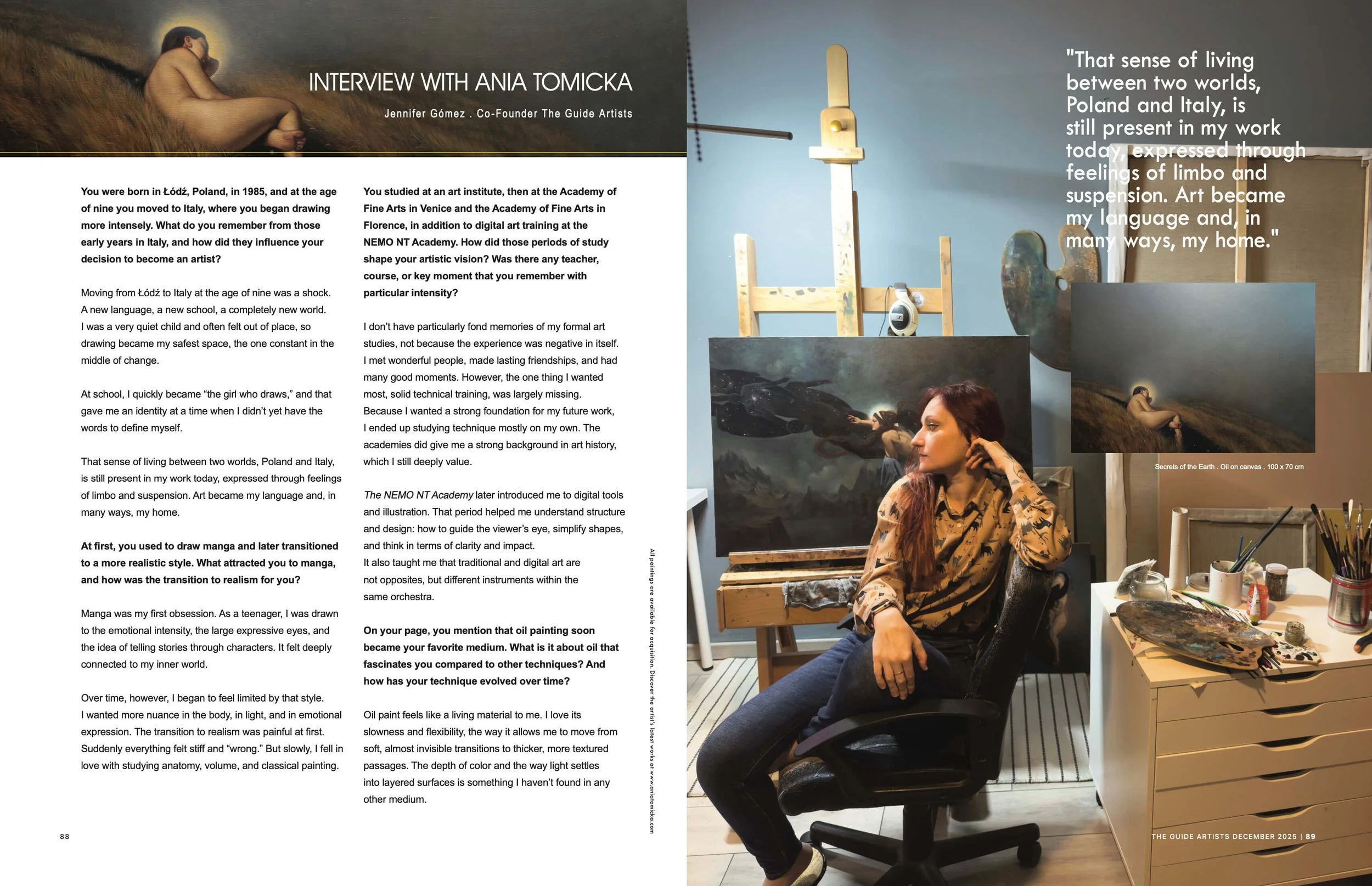

Moving from Łódź to Italy at the age of nine was a shock. A new language, a new school, a completely new world. I was a very quiet child and often felt out of place, so drawing became my safest space, the one constant in the middle of change.

At school, I quickly became “the girl who draws,” and that gave me an identity at a time when I didn’t yet have the words to define myself.

That sense of living between two worlds, Poland and Italy, is still present in my work today, expressed through feelings of limbo and suspension. Art became my language and, in many ways, my home.

At first, you used to draw manga and later transitioned to a more realistic style. What attracted you to manga, and how was the transition to realism for you?

Manga was my first obsession. As a teenager, I was drawn to the emotional intensity, the large expressive eyes, and the idea of telling stories through characters. It felt deeply connected to my inner world.

Over time, however, I began to feel limited by that style. I wanted more nuance in the body, in light, and in emotional expression. The transition to realism was painful at first. Suddenly everything felt stiff and “wrong.” But slowly, I fell in love with studying anatomy, volume, and classical painting.

You studied at an art institute, then at the Academy of Fine Arts in Venice and the Academy of Fine Arts in Florence, in addition to digital art training at the NEMO NT Academy. How did those periods of study shape your artistic vision? Was there any teacher, course, or key moment that you remember with particular intensity?

I don’t have particularly fond memories of my formal art studies, not because the experience was negative in itself. I met wonderful people, made lasting friendships, and had many good moments. However, the one thing I wanted most, solid technical training, was largely missing. Because I wanted a strong foundation for my future work, I ended up studying technique mostly on my own. The academies did give me a strong background in art history, which I still deeply value.

The NEMO NT Academy later introduced me to digital tools and illustration. That period helped me understand structure and design: how to guide the viewer’s eye, simplify shapes, and think in terms of clarity and impact.

It also taught me that traditional and digital art are not opposites, but different instruments within the same orchestra.

On your page, you mention that oil painting soon became your favorite medium. What is it about oil that fascinates you compared to other techniques? And how has your technique evolved over time?

Oil paint feels like a living material to me. I love its slowness and flexibility, the way it allows me to move from soft, almost invisible transitions to thicker, more textured passages. The depth of color and the way light settles into layered surfaces is something I haven’t found in any other medium.

In the beginning, I wanted everything to be hyper-smooth and perfectly polished. Over time, I became more interested in layering, transparency, and allowing subtle traces of the process to remain visible. Now I aim for a surface that feels refined but not sterile, something that can breathe.

You’ve also worked with digital art and illustration, although your main focus seems to be on traditional painting. How do you balance digital and traditional art in your creative process, and what role does each one play in your work?

Digital tools are, for me, a playground and a planning space. I use them to sketch, test compositions, adjust colors quickly, or combine references. They allow me to make decisions without fear.

Traditional painting is where the real emotional weight resides. The slowness, the resistance of the material, even the smells, all influence how I feel and what ultimately appears on the canvas. Digital work supports the birth of an idea; oil painting is where that idea becomes intimate and tangible.

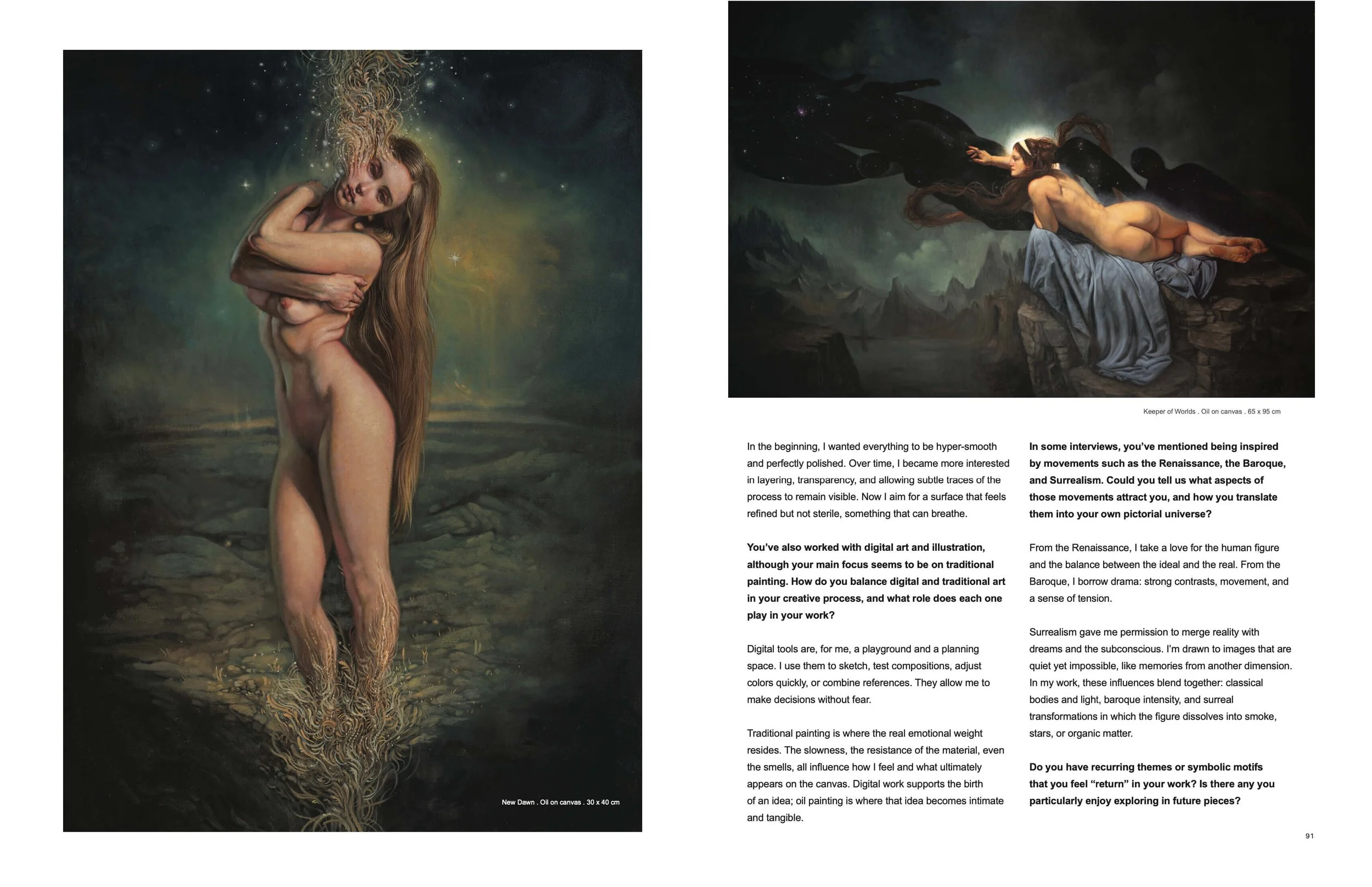

In some interviews, you’ve mentioned being inspired by movements such as the Renaissance, the Baroque, and Surrealism. Could you tell us what aspects of those movements attract you, and how you translate them into your own pictorial universe?

From the Renaissance, I take a love for the human figure and the balance between the ideal and the real. From the Baroque, I borrow drama: strong contrasts, movement, and a sense of tension.

Surrealism gave me permission to merge reality with dreams and the subconscious. I’m drawn to images that are quiet yet impossible, like memories from another dimension. In my work, these influences blend together: classical bodies and light, baroque intensity, and surreal transformations in which the figure dissolves into smoke, stars, or organic matter.

Do you have recurring themes or symbolic motifs that you feel “return” in your work? Is there any you particularly enjoy exploring in future pieces?

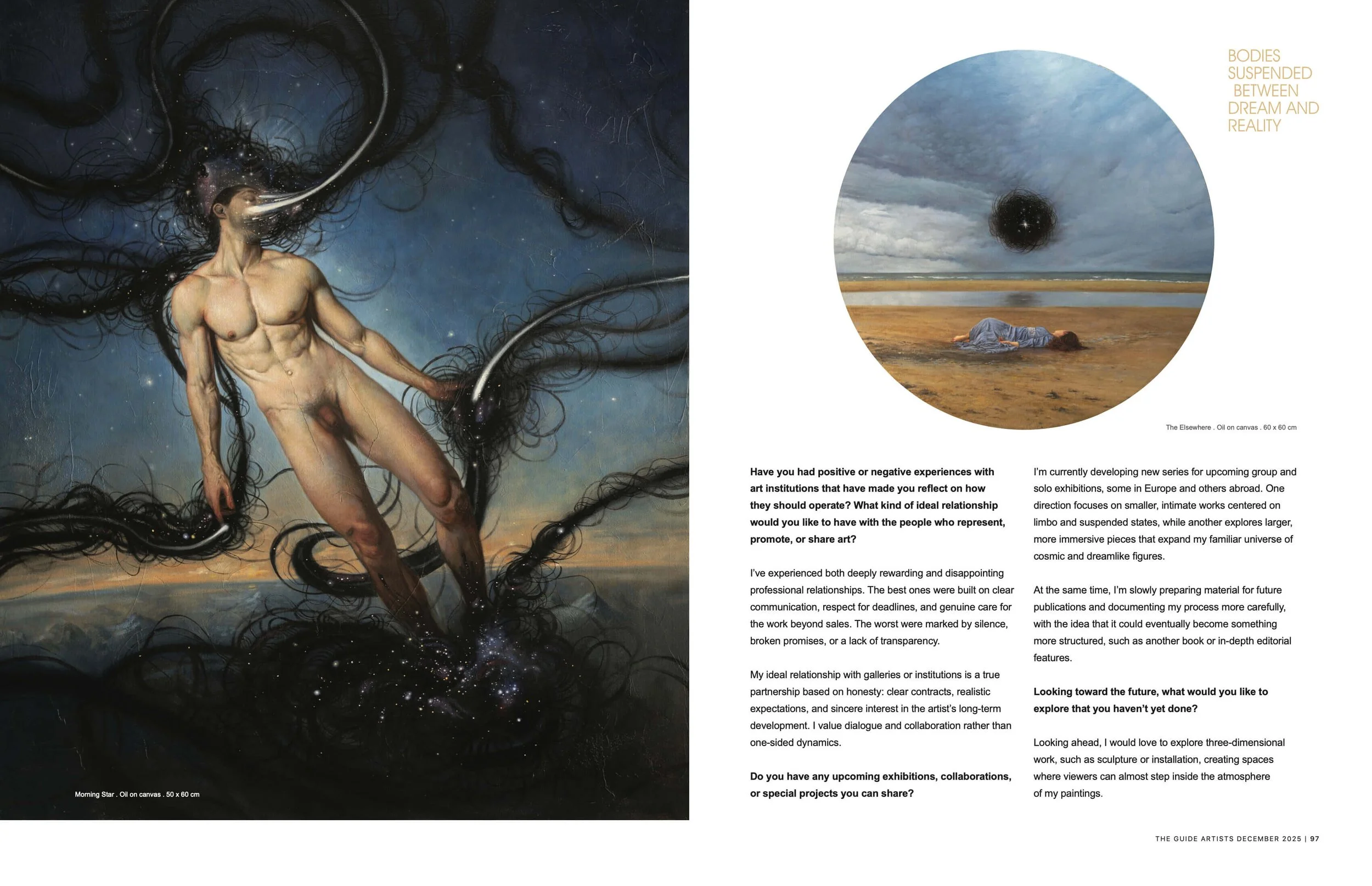

I often return to figures in states of suspension, falling, floating, or existing in some form of limbo. Hair turning into smoke, bodies cracking open, wounds revealing cosmic spaces, small particles of light or stars, these motifs appear again and again, almost instinctively.

A recurring theme in my work is the fragile boundary between body and soul, and the way inner pain can become transformation. I want to continue exploring what I think of as “landscapes of the soul”: foggy forests, ruins, and spaces that feel psychological as much as physical.

Could you describe your process from idea to finished piece — how you approach a new painting, the sketch, the mistakes, the moments of doubt, up to

the final resolution?

A painting usually begins with a feeling rather than a clearly defined concept. I might glimpse a pose, a face, or a small mental image that keeps returning. I create small sketches and sometimes digital studies to find the right composition and values.

On the canvas, I start with an underpainting to establish structure and light, then gradually build color and atmosphere in layers. The middle stage is always the hardest. The painting feels awkward, and doubt takes over. I’ve learned to accept this “ugly phase” as an essential part of the process.

The final stage often comes down to a few decisive choices: softening an area, removing something I liked, or adding a subtle detail in the face or the light. At a certain point, the painting stops feeling like a problem to solve and starts feeling like a living presence. That’s when I know it’s finished.

What has been the greatest technical or creative challenge you’ve faced in a work?

Large, complex works with multiple figures and strong symbolic content have been my greatest challenges. Managing composition, anatomy, and atmosphere at that scale is both mentally and technically demanding.

In one particular piece, I struggled for months to keep the skin luminous against a very dark, almost cosmic background. I had to repaint sections multiple times and accept that some ideas wouldn’t survive. That experience taught me that sometimes you have to risk “ruining” a painting in order to make it honest and alive.

Being an artist also means handling the business side — visibility, social media, promotion... In a recent interview, you mentioned that one of the challenges was balancing creation with the more commercial side. How do you experience that balance? What strategies have you found helpful to maintain your artistic integrity without neglecting visibility?

For me, the business side of being an artist is both a blessing and a burden. Social media allows me to reach people all over the world without intermediaries, which is incredibly powerful. At the same time, the constant pressure to post, stay visible, and perform online can drain the energy I need for painting.

What helps is creating boundaries and systems. I try to dedicate specific days or time blocks to content creation, emails, and promotion, so my studio time remains as protected as possible. I focus on sharing my process honestly rather than chasing trends, showing sketches, works in progress, and thoughts behind the work.

I remind myself that visibility is not the goal, but a tool. The real goal is to continue developing my inner world and connecting with people who resonate with it. When a form of promotion feels as though it would distort the work or reduce it to something superficial, I prefer to say no, even if it promises quick attention.

How has the art world (galleries, the internet, social networks, online sales) changed since you started, and how does it affect your practice today?

When I began, the artistic path felt more centered around galleries and physical exhibitions. Today, the landscape is much faster and more digital: online galleries, Instagram, direct sales, NFTs for a time, everything shifts quickly.

The advantage is the ability to build an audience independently, without relying entirely on institutions. The downside is saturation and the constant sense of competing for attention.

In my practice, I try to maintain a “slow core”, long-term painting projects and deep focus, while also accepting that some of this work must be translated into formats that function in the online world.

Have you had positive or negative experiences with art institutions that have made you reflect on how they should operate? What kind of ideal relationship would you like to have with the people who represent, promote, or share art?

I’ve experienced both deeply rewarding and disappointing professional relationships. The best ones were built on clear communication, respect for deadlines, and genuine care for the work beyond sales. The worst were marked by silence, broken promises, or a lack of transparency.

My ideal relationship with galleries or institutions is a true partnership based on honesty: clear contracts, realistic expectations, and sincere interest in the artist’s long-term development. I value dialogue and collaboration rather than one-sided dynamics.

Do you have any upcoming exhibitions, collaborations, or special projects you can share?

I’m currently developing new series for upcoming group and solo exhibitions, some in Europe and others abroad. One direction focuses on smaller, intimate works centered on limbo and suspended states, while another explores larger, more immersive pieces that expand my familiar universe of cosmic and dreamlike figures.

At the same time, I’m slowly preparing material for future publications and documenting my process more carefully, with the idea that it could eventually become something more structured, such as another book or in-depth editorial features.

Looking toward the future, what would you like to explore that you haven’t yet done?

Looking ahead, I would love to explore three-dimensional work, such as sculpture or installation, creating spaces where viewers can almost step inside the atmosphere of my paintings.